<em>Thean Ly’s painting “Zombie” (untitled in Khmer) is now owned by the Maddox Jolie-Pitt Foundation. Photograph: Thean Ly</em>

Thean Ly’s painting “Zombie” (untitled in Khmer) is now owned by the Maddox Jolie-Pitt Foundation. Photograph: Thean Ly

Thean Ly’s painting “Zombie” (untitled in Khmer) is now owned by the Maddox Jolie-Pitt Foundation. Photograph: Thean Ly

Amid the chaos of paint tubes, brushes and plastic containers within an arm’s reach of Roeung Sokhom’s painting-in-progress, “Look Back”, lies a snapshot of Pol Pot.

“That’s a leftover,” Sokhum says. “I’m already done with them,” he explains, referring to the Khmer Rouge – the subject of two paintings he finished after returning from France early last year. One places Pol Pot and those currently on trial for genocide in the centre of sunflowers grasping towards the sun; the other is a portrait of S-21’s prison chief comprised of a collage of thumb-sized photos of Kaing Guek Eav, Duch, with a blood-soaked krama around his neck.

But Sokhum, and the rest of the close-knit village-born painters and sculptors in Battambang, are now focused on the present: daring work that shows Cambodia as it is today laid bare – including sculptures which draw attention to the plight of society’s harangued and oppressed, from beer girls to protestors, and an entreaty to young people to ‘Occupy yourselves’.

(L) Red Perspective, by Thean Ly; (R) A studio shared by painters Roeung Sokhom and Bo Ravy. Photograph: Long Kosal

“Look Back” feels fresh, both in concept and execution. Sokhum, bored with painting on canvas, switched to horizontal slats of bamboo shoots tied together with string. The bamboo-shoot background subverts a traditional proverb (“shoots grow into bamboo”) used to reinforce the idea that people are born into their social class – an idea Battambang art is demolishing.

“Children of farmers are expected to become farmers,” Sokhum explains.

The scene itself, however, is quite traditional: an elderly waffle vendor at a market. Sokhum says he wants to remind young people to recall the care their parents gave them and return it.

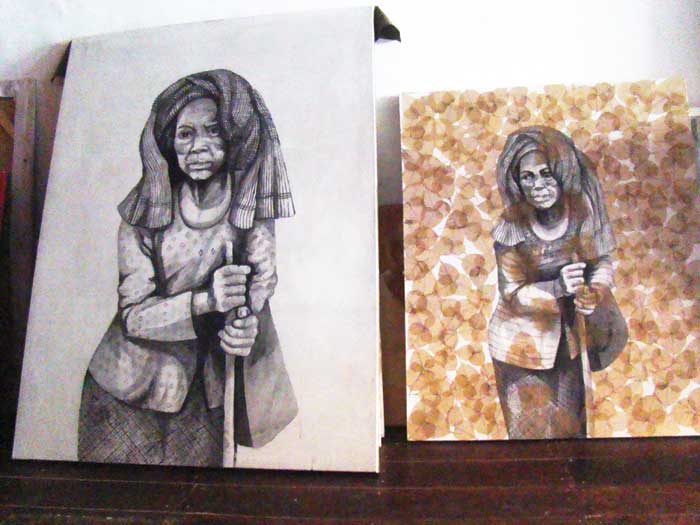

Caring is also key to the latest exhibition by fellow Battambang native Ben Thynal, at the Intercontinental Hotel. The show will comprise 13 large canvases of elderly and impoverished beggars and vendors, some so frail they can barely sit upright, all with their eyes averted. This series, too, is based on a Khmer proverb, one reminding youths to care for their parents during their “moonlight” years.

Thynal’s portraits, like Sokhum’s, are based on snapshots, and he also borrows materials rich with local meaning, namely bodhi tree leaves. He’s covered the portraits with leaves that have been soaked for 15 days, making them nearly translucent, to illustrate how nature encompasses human life.

Thynal says he is well aware of the irony of placing these portraits at a five-star hotel, where the subjects would never get past security, but his goal, he says, is “for people to see them the way I do”.

“They are always alone when they are poor,” he says.

He has himself run out money and the care of others helps him to make his way. With no studio of his own, he’s working on his latest series at Make Meak (Make Sky) gallery owned by Mao Soviet, one of the oldest galleries and a focal point for the group of artists.

“What’s amazing here is the spirit,” says painter Thean Ly, from his studio above his father’s shoe-repair shop. About two years ago he gave up a lucrative career as a graphic designer in Phnom Penh to move home to Battambang so that he could paint freely.

For his upcoming show at JavaArts and his first solo exhibit (Surviving) he has painted a series of portraits of submerged individuals, with only their noses above water.

Ly describes the working environment as one of collaboration and mutual encouragement. It’s also inexpensive, he adds.

Most Battambang artists with studios rent studios in groups of two or three to cover the monthly rent of US$50 to $80.

Beggar 1 (R) and Beggar 2 (unfinished) will be at Ben Thynal’s exhibit at the InterContinental from January 17. Photograph: Ben Thynal

It’s a step forward: two years ago local artists were making art in the rooms that they slept in. A total of 15 now have studios, according to Soviet – the man Ly says is the glue that binds the Battambang artists together.

At 32, Soviet is among the oldest of the artists working here, though he prefers to be described as among the first generation to graduate from the NGO art school Phare Ponleu Selpak (The Brightness of Art). He began with quick sketch classes on December 21, 1995 and gradually immersed his entire imagination into art.

He turned from painting to sculpture in 2010 with his first installation, “The Tongue”. It hangs now from the ceiling of the floor above Make Maek in a cluttered space that even if it were empty would be far too small for it: a nine-metre undulating, magic-carpet-like ride of used bottle caps wired together (15 to a row).

“The Tongue” is startling and joyful a response to Cambodia’s often harshly intolerant society, triggered initially by the constant gossip Soviet and his wife endured during the six years they lived together before marrying two years ago. Soviet says the thousands of used bottle caps also represent the women hired by breweries to sell their products in beer gardens, where they are often subjected to extreme sexual harassment by customers and disrespected by neighbors who regard them sex workers.

It is possible, too, to see the bottle caps, which Soviet has been using since 2006, as an invitation to open art and imbibe the ideas, craftsmanship and creativity that emanates from it. This is an interpretation that he says was not consciously intentional.

“My art does not sell well,” Soviet says, noting that only two of the seven pieces of his joint exhibit “The Black Wood” (with American photographer Tim Robertson) sold last year. The pieces were abstract paintings on charred wood from a deforested area. The show focused on what Soviet describes as the two most pressing issues facing Cambodia: deforestation and forced evictions.

“It was the first exhibit to go against the government,” one Battambang artist, who preferred not to be named, said.

“Art is news,” Soviet explains as he strings together rows of bottle caps for his latest sculpture “Whistle”, which will be installed at Romeet Gallery in February. “Only art can show what is going on in Cambodia. People who get their news from TV don’t even know what is going on 25 kilometers outside the city.”

Soviet is nearing completion of “Whistle”, perhaps his most ambitious and overtly political work yet. The idea behind it is not to sound the alarm, he says, though he touches his chest with his palm as he says this, showing that he too is aware that the sound of a whistle also triggers a sense of alarm in him.

There are two concepts behind the piece, he says. First, police use whistles to control protesters and second traffic police use them to extort bribes from motorists. The bottle caps are intended to continue to draw attention to the plight of “beer girls”, but they are also taking on a bigger meaning, encompassing the crimes committed as a result of intoxication, such as rape, Soviet says.

He comes across as a patient artist, one who is a few steps ahead of every question. He responds “I don’t care” when asked if he is concerned he might upset the police with “Whistle”, in a nonchalant tone. He’s got his eye on a bigger picture, glimpses of which can be seen in Make Maek. It offers art classes for children, a PC for artists to store their slides on, shelves of books, movie nights and T-shirts with Soviet’s slogan: “Occupy Yourself”.

When it closes, the two wooden tables on the sidewalk outside serve as a meeting place for artists struggling to make art and ends meet at the same time. Their conversations are casual, almost directionless, but if you listen carefully to Battambang artists there is the sound of streams of consciousness merging: an accidental collective that is increasingly determined to make socially engaging art that sustains and inspires its locale.

Contact PhnomPenh Post for full article

SR Digital Media Co., Ltd.'#41, Street 228, Sangkat Boeung Raing, Khan Daun Penh, Phnom Penh, Cambodia

Tel: +855 92 555 741

Email: webmasterpppost@gmail.com

Copyright © All rights reserved, The Phnom Penh Post