Co-founder of The Phnom Penh Post, Michael Hayes.

Michael Hayes has many strings to his bow, but none quite surpass the distinction of being the co-founder and former publisher of The Phnom Penh Post. As the man behind the first English-language newspaper in the Kingdom, Michael’s determination and resilience in the face of overwhelming obstacles in making The Post a reality is a testament to his passion for journalism and press freedom. Michael spoke to The Post about the challenges he encountered in the early days of the publication and provides his opinion on the current state of media in the digital world.

The Phnom Penh Post is approaching its 25th birthday. I’m sure there were numerous times when you thought you wouldn’t see this milestone. For you personally, how significant is the 25th anniversary for you?

I am, of course, very glad that The Post is still alive and kicking. It plays an extremely valuable role in informing readers about current events in Cambodia and that is both useful and necessary for those of us who follow what is going on here.

Michael Hayes with a chaise lounge and a box of ready-to-eat meals for a 10-day expedition by elephant into the wild jungles of Mondulkiri province. Tim Page

You once said, “How the paper survived is an absolute mystery to me.” It seemed like you lacked faith in the longevity of the newspaper. What kind of personal qualities do you attribute to being able to persevere with keeping the paper afloat?

The years I ran The Post, from 1992 to 2008, were a long, seemingly endless struggle to keep the paper alive financially and politically. Almost every month was a battle just to make payroll. I used to tell people, “I’ve never been paid so little to worry about money all the time.” The simple answer to your question was to maintain an attitude of “never give up” and repeat that mantra every day after day after day. But there were plenty of times when I doubted I had the strength to go on. All too often I felt like a rat on a treadmill in some bizarre, scary laboratory, surrounded by constant threats all the while wondering if and when there would ever be a break. There wasn’t.

How do you feel The Post has contributed to or influenced the important political and societal events that have played out in Cambodia?

This is a very difficult question to answer, and one I’ve been asked repeatedly. It would be a good subject for someone’s PhD dissertation. The short answer is not very much. However, at the very least, The Post has been able to keep people informed and provide a reliable record of current Cambodian history. I’ve said many times that if The Post was successful it would be cited in footnotes in books written by scholars that were read by about 100 people. That has, in fact, turned out to be the case, which is personally satisfying. Most recent books on the Kingdom make regular references to Post articles. If I’m not mistaken, Sebastian Strangio’s recent book Hun Sen’s Cambodia wins the prize with about 180 references to Post articles in his footnotes.

I should also add that in reply to The Post’s detractors, [who say] that it provides too much “negative news” on Cambodia or that it “criticises” the government unfairly, I’m not aware of one foreign investor that decided not to invest here because of Post reporting. The Kingdom’s average 7 percent annual growth rate over more than a decade is ample evidence of this.

A veteran Khmer Rouge cadre, missing several fingers and an eye, tells reporters to back off during a visit to central Kampong Thom. Michael Hayes

How would you describe the way the journalists and editors at The Post operated when you were still at the paper?

Everybody was flat out every day, almost all the time. Burnout and turnover were high and pay was minimal, but I think we all felt a deep sense of satisfaction with the final product. And I know my Cambodian reporters felt a certain sense of pride by being part of the process. That was especially rewarding because they were writing about their country, their people and their problems and achievements. (Keep in mind that before The Post went daily we only published news about Cambodia.) There were numerous occasions, on very sensitive stories, when I asked my Cambodian reporters if they were sure they wanted their names on the by-line, noting that we could print “By Post staff”. Almost without hesitation, they all said, “Yes, this is my country and I’m proud to be able to report these kinds of issues.” My Cambodian reporters were gutsy and I was so honoured and thankful to have them on board. They are the unsung heroes of this ongoing story.

Can you recall any interesting memories or stories from your time at The Post? Is there anything that really stands out when you reflect back on your years at the paper?

There are hundreds of crazy, scary, funny, historic stories to tell, too many for this Q&A. You’ll have to wait until my book on the history of The Post comes out to read them.

Do you still continue to read The Post?

I read The Post and The [Cambodia] Daily every day.

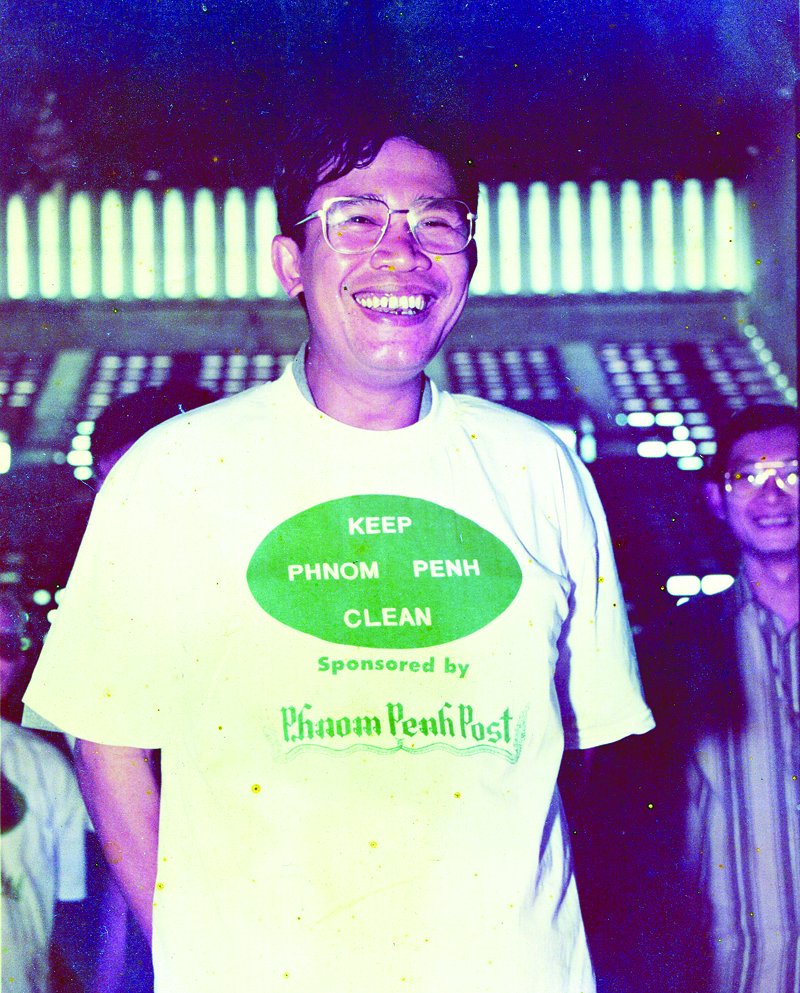

Prime Minister Hun Sen took the lead in promoting a ‘Keep Phnom Penh Clean’ campaign sponsored by The Phnom Penh Post in 1993. Photo supplied

What are your opinions on the state of press freedom in Cambodia? Has much progress been made on that front?

Press freedom will always be at risk in Cambodia because the political culture doesn’t appreciate or understand the role of an independent media. This is not unique to Cambodia, but a problem all over the world. Many politicians believe that if a paper prints an article that makes them “look bad” then the paper has some kind of hidden agenda, such as that cited by the Royal Government recently about The Post and The Daily, to “overthrow the government”. These accusations are totally unfounded but there is not much anyone can do about it. Cultural mind-sets never change quickly. As a historical aside, many years ago we faced the same accusations from the government. I wrote to HE Sok An and offered him a free full page every issue to print whatever the government wanted but I never heard back from him.

You started The Phnom Penh Post when there was barely any competition in the market. Now there are two other English-language newspapers, and there is also Facebook and the general trend of digitisation threatening the traditional model of the media business. Given these external forces at play, how does an established, long-running organisation like The Post stay relevant and compete with these rivals to remain viable in the future?

We had competition straight away. The Post’s inaugural issue came out on July 10, 1992. On July 13 The Cambodia Times started, the paper run by the same people who now publish and fund the Khmer Times. But to answer your question, if there were a secret recipe for success out there on how to compete in the current media environment, I would give it to you. I don’t have it.

Royal Cambodian Armed Forces (RCAF) and Khmer Rouge soldiers celebrate after Ieng Sary agrees to defect along with his troops to government in Pailin in 1996. Michael Hayes

Media outlets all around the world are facing obstacles, with print circulation and ad revenue in general decline. What are your hopes for the future of The Post?

The future will be rocky, as it is worldwide. Work harder, longer hours and be ready to take a pay cut. A lesser-paid job is better than no job at all.

Any other comments?

Dig, dig, dig and keep on digging to print the truth in a fair and responsible way. The Cambodian people deserve nothing less.

Contact PhnomPenh Post for full article

Post Media Co LtdThe Elements Condominium, Level 7

Hun Sen Boulevard

Phum Tuol Roka III

Sangkat Chak Angre Krom, Khan Meanchey

12353 Phnom Penh

Cambodia

Telegram: 092 555 741

Email: [email protected]