Cambodia’s economy has benefitted from a construction boom and real estate-related sector growth, such as these in Chamkarmon district, for years. Yousos Apdoulrashim

In the last 10 years, the property and construction sectors have propelled Cambodia’s economy. But rising borrowings threaten to dampen its future unless something is done soon

They say all good things must come to an end, perhaps not “the” end. A slowdown in real estate and construction credit growth, in light of the current economic landscape, might not be a bad thing.

Generally, overall credit growth is good for a country because it spurs domestic consumption and stimulates the economy.

Despite the healthy economic indicator, experts raised the flag over the high trajectory in the real estate and construction sectors.

For nearly a decade, Cambodia has bucked soft property market trends in the region, recording a robust property and construction growth that were buoyed by good economic performance and speculation.

The credit expansion was fed by strong foreign investments in these sectors, particularly in the high-end and mid-range segments that catered to foreign demand and a rising domestic market.

“Huge inflow of investment from abroad, especially from China, is the main factor leading to an increase in property prices and their potential oversupply,” said Associate Prof Samreth Sovannroeun, an economics lecturer in a Japanese university.

As the Covid-19 outbreak threatens to cripple global economy and weaken growth sectors, credit risks are becoming more apparent.

Between 2000 and 2019, some 48,004 construction permits with a total investment of $51 billion were issued by the government.

Up 55 per cent in 2019, nearly 4,500 projects valued at $9.3 billion were approved in 2019. Total investment value rose 60 per cent from $5.8 billion in 2018.

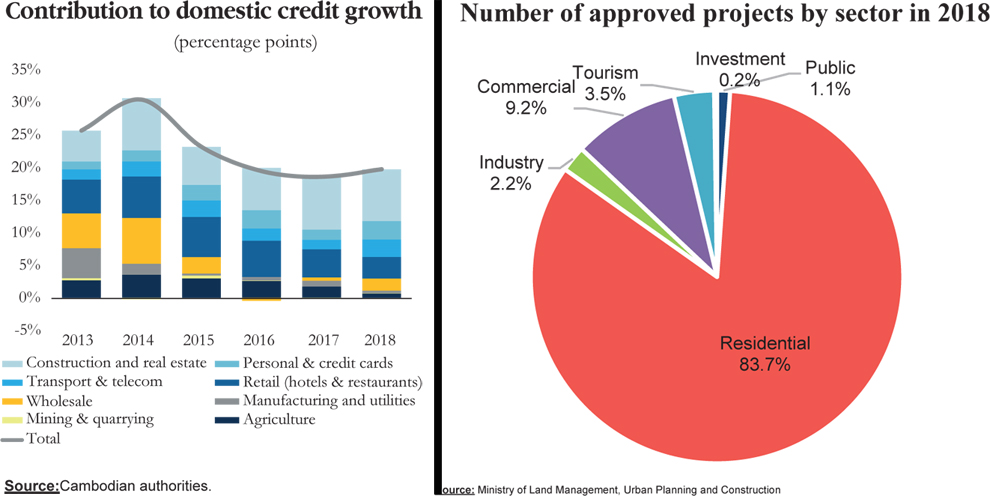

In Cambodia, bank loans to both sectors constituted 17.1 per cent of the overall sum, up 35.4 per cent in 2018 from 33 per cent in 2017. As for foreign direct investments (FDIs) in 2018, 20 per cent of the total was for the construction and real estate sectors, which grew 27.5 per cent from 2017.

In 2019, International Monetary Fund (IMF) directors called for prompt actions to moderate it, including through additional macroprudential measures and broad-based policy responses to address risks stemming from the real estate sector.

Private sector credit, underpinned by the two sectors, had accelerated and was expected to grow around 28 per cent in 2019, and moderate to 25 per cent in 2020.

“Financial conditions have been accommodative and credit has accelerated, leading to a widening of the bank credit-to-gross domestic product (GDP) gap, estimated at 17 per cent,” IMF said in its Article IV consultation paper in December 2019.

The percentage was above the Bank of International Settlements’ threshold of 10 per cent, which acts as an early warning indicator for banking distress.

The Kingdom’s central bank counts the high level of credit growth to the construction sector as well as active mortgage financing by property developers that have yet to be firmly regulated, as internal risks.

Between 2012 and 2018, credit to construction, real-estate activities and mortgages has expanded to 27.6 per cent of total credit from 16.5 per cent.

“While a credit squeeze [reduction of credit availability] can have negative impacts in those sectors, negative shocks such as a property overhang can hurt the financial sector and overall economy,” Sovannroeun said.

Given the risk, the National Bank of Cambodia (NBC) has made repeated calls over the real estate sector’s dependence on external funding and domestic credit.

“Vulnerabilities from rapid credit growth, especially to real estate-related sectors, have prompted discussions on potential policy measures to mitigate potential risks,” the NBC said in 2018.

It is also worried that if external demand and the domestic economy weakened, the sector could see an oversupply.

True enough, US-based real estate service and investment firm CBRE Cambodia forecasts supply to increase 55 per cent with 28,000 condominium units in 2020 from last year.

About 24 per cent of that is made up of high-end units, 46 per cent mid-range and 30 per cent affordable ones.

CBRE Cambodia associate director James Hodge said developers are expected to face challenges in condominium development as the market becomes more competitive.

“Rental rates for this market segment could experience some downward pressure with increasing supply,” he said.

Property bubble or overhang?

Often, industry players find it hard to predict a bubble despite the highly energetic sectors and a likely outcome of supply outweighing demand.

But what can be observed instead, is an overheating trend on the back of a rapid credit rise and construction boom.

If it is not well regulated and monitored, a property overhang in the luxury real estate and condominium market can happen, Sovannroeun cautioned.

“In the future, although it may depend on the performances of Chinese and global economies, there can be a property overhang, especially in the luxury real estate and condominium markets which depend mainly on foreign buyers.

“The occurrence can have various impacts on the Cambodian economy,” he added.

It can lead to a significant decrease in property prices and negatively affect the business performance of real estate and construction firms.

As a result, unemployment can increase and adversely impact the overall economy.

“While the main funding for large projects is from foreign sources, the general dip in property prices could have adverse consequences on the domestic financial sector, which is the main credit provider for housing loans and investments of smaller-scale projects.

“Falling property prices can raise the rate of non-performing loans, exposing the domestic financial sector to higher risks,” Sovannroeun said.

Jayant Menon, a visiting senior fellow with Singapore’s Institute of Southeast Asian Studies-Yusof Ishak Institute, opined that a correction in the overheated property market is long overdue.

“A cooling-off now is inevitable. As long as a major and sudden crunch is averted, it [cooling off] will bode well for the longer-term health of the sector,” he said.

Meanwhile, economist Chheng Kimlong said supply in the property sector peaked in the last two years or so due to speculation-driven demands for medium and high-end housing units.

In fact, property sector sales have reduced as inflows of private investment have dried up in the current economic landscape.

“But the low-cost housing market remains strong,” said Kimlong, who is attached to independent think-tank, Asian Vision Institute.

He thinks that the high credit growth trend in these sectors will not prolong but there is a likelihood of it happening in a sub-sector.

“High growth [in both the major sectors] used to be before the end of 2019. As of now, there is a downward trend as demands in the real estate sector have stagnated.

“Depending on real estate and construction sectors, low-cost housing demands will be high and credit in this sub-sector is expected to grow, albeit at a slower rate,” Kimlong said.

Less room to manipulate

In one of NBC’s reports, the credit-to-GDP gap is explained as the difference between credit to GDP ratio and its long-term trend.

Now, anything above 10 per cent indicates that credit may have grown to an excessive level relative to GDP. While the measurement of the gap was 17 per cent in 2019, it has been on an uptrend, riding above 10 per cent since 2015.

This presents some risks associated with the real estate and construction sector as the latter constitutes one-third of the total private sector credit and because of the low level of economic diversification, a shock to the real estate and construction sector can shake the financial sector.

“Responding to this sector can be risky. [In any case] the government does not have much room to manipulate the financial policy as the economic base is very narrow,” Kimlong said.

Beyond the real estate and construction sectors, bank credit was boosted by a surge in incomes, demand and availability of various financial services, and consumption needs, especially for purchasing goods and mortgage.

But, rising consumption could pose a risk if consumers do not spend, kicking up the risk of indebtedness especially in microcredit and microfinance as it is associated with default rate.

“There are general socio-economic implications of rising indebtedness within the lower-income group. For example, they might borrow to finance their micro-and-family businesses but part of the loan is used for other non-productive activities, such as weddings, religious ceremonies, and children’s education,” he said.

Can the risk be minimised?

The short answer is yes. Back in 2018, the NBC noted that while credit to both the supply side (construction and real estate-related activities) and the demand side (mortgages) rose fast, the quality of construction loans deteriorated due to delays in some construction projects, pushing up non-performing loan ratio.

But efforts to lower the risk have been thought up including the imposition of higher risk weights on loan applications for the real estate and construction sectors.

Sovannroeun suggested that local financial institutions increase its reliance on domestic sources of funding, as this would reduce exposure to external shocks, and minimise their risk.

Internally, the availability of domestic financial resources can be enhanced by promoting the usage of riel for transactions and deposit, and developing a riel-dominated capital market.

“Banks can also be made to raise their minimum reserve requirements so that lending capacity to the risky sectors can be lowered.

“However, this should be done gradually and with caution to avoid any adverse effect on credit availability and financial inclusion,” he added.

Similarly, World Bank said macroprudential measures such as limiting banks’ exposure to construction and real estate should be considered.

Given prolonged expansion of domestic credit growth, strengthening oversight capacity and crisis preparedness in the financial sector should be an important first step.

And there is no better time than now. Previously, the surge in FDI inflows had sustained the construction boom while masking the financial sector’s vulnerability after years of rapid lending growth.

Unfortunately, such large foreign capital inflows might not sustain, particularly in the current global uncertainty and slowdon in China.

“The drying up of FDIs in the construction sector could result in a collapse in prices and expose financial sector vulnerabilities,”it said in a report last year.