Striker Timothy Chiemerie (back) prepares for the pitch with teammates. Victoria Mørck Madsen

Despite its many shortcomings, expat players find Cambodia’s football scene an attractive springboard

For 38-year-old veteran midfielder Masahiro Fukasawa, the greatest moment of his professional football career came at the beginning of a six-year stint playing at the highest level in his homeland, Japan.

“It was my debut game for Yokohama Marinos in 1998 against Cerezo Osaka. We lost, but I scored, so I was very happy,” he recalled.

“[The goal] was only from about three metres out, but it was still special,” he said laughing.

After leaving Japan in 2004, Fukasawa embarked on a footballing odyssey that took him through North America and four Southeast Asian countries, before eventually landing in Cambodia last year.

Now captain of NagaWorld FC, Fukasawa says he maintains the same passion for the game he had as a youngster, despite often playing in front of hundreds of people rather than the tens of thousands he used to.

For Fukasawa, while the Cambodian league trails others in the region in terms of organisation and the quality of football, development has been noticeable even in the short time he has been here.

Nigerian Anayochukwu Ugwu cools off with a teammate after practice.Kimberley McCosker

“Last year, there were only two stadiums, and at the Old Stadium we couldn’t even get into the locker room, so we would have to change in front of the supporters,” he said.

“This year, they have provided locker rooms, so we can get changed and have a shower. These are tiny things, but if you correct the tiny things, it makes a big difference.”

A gateway to the world

Fukasawa’s time in Cambodia’s Metfone C-League may represent some of the later years of his career. But many foreign players see Cambodia as a stepping stone to a brighter future.

“I am playing [here] to move to Thailand, Singapore or, if possible, Europe,” said 21-year old striker Timothy Chiemerie, who arrived in Cambodia from Nigeria in June.

“After this season, if I have the opportunity, I will leave.”

Nigerians make up the largest nationality group among foreign players in Cambodia, with more than 20 currently playing in the league.

Players from other African nations including Cameroon, Ivory Coast and Guinea are also plying their trade here.

Many who spoke to Post Weekend said that while wages were not necessarily higher in Cambodia than in Africa – and attendances at professional matches in their homelands usually dwarf those seen here – the greater number of foreigners playing in Cambodia and proximity to more lucrative leagues offers significantly more exposure.

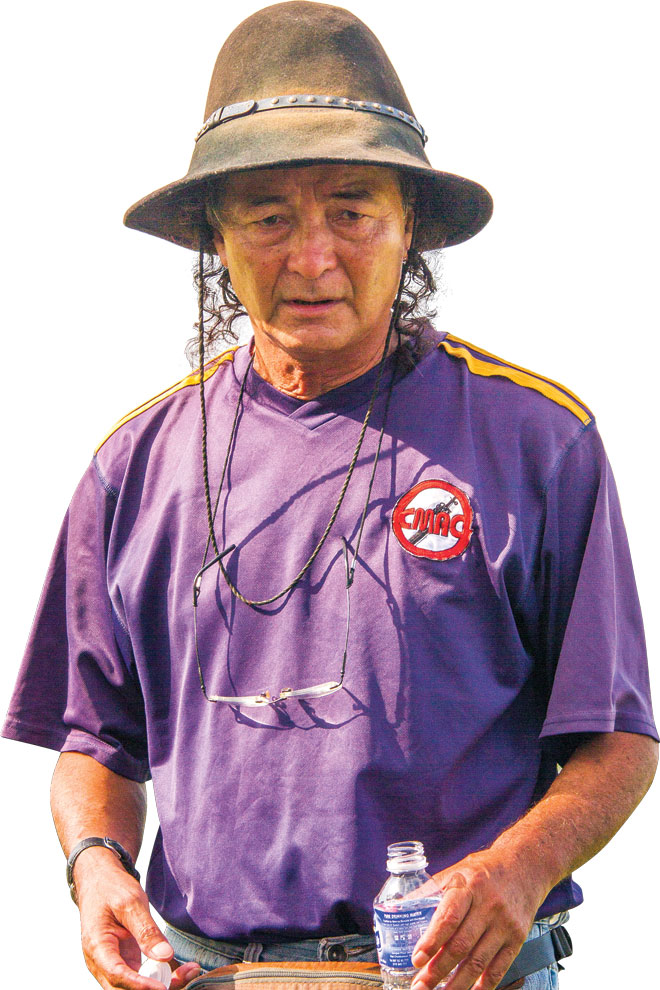

Masahiro Fukasawa- Charles Parkinson

Recent examples of players who have secured moves abroad after excelling in Cambodia include Nigerian strikers Justine Uche Prince and Julius Chukwuma, who moved to Thailand in 2010 and 2011, respectively, after finishing as top scorers for their teams.

Yet with teams only allowed five foreigners on their squad and three on the pitch at any one time, competition for a place can be stiff.

For Chiemerie, hopes of picking up a slot on the roster of one of the bigger clubs were replaced by the realisation that there are dozens of foreign footballers here unable to find a club.

He was eventually offered a short-term contract by CMAC United FC – a team in its first season in the top flight, originally set up to raise awareness about the work of national demining organisation Cambodian Mine Action Center.

While Chiemerie had to accept a wage “just enough for rent and food”, many of his teammates are paying to play.

“Our team is mostly amateur and you pay a membership fee,” said CMAC United’s Dutch team manager Billy Barnaart, who played professionally in Belgium in the 1970s and has been involved in football in Cambodia for more than 20 years.

“Even if we go and play overseas, in Thailand for example, the players pay for their registration and their travel,” he said. “Those that earn a good wage [in their non-football jobs] help the others out.”

One of those putting his hand in his pocket is 29-year-old NGO worker Tony Janzen, who was playing under Barnaart for amateur expat team Bayon Wanderers when the Dutchman was asked to take over CMAC United as it launched in the top flight.

Indiana native Tony Janzen (left) is a striker at CMAC United.Kimberley McCosker

“I just wanted to help them out,” says the six-foot striker, whose only previous experience playing competitive football came at college in his native Indiana.

“CMAC is doing important work and I wanted to help bring attention to that,” he said.

Benefits from abroad

CMAC United relies on the benevolence of some of its foreigners to deal with the financial strain of playing in the top tier.

But at the other end of the spectrum, a development drive among a handful of relatively affluent clubs has foreign players at its core.

“Foreign players promote football development very well,” said Lay Sothea, director of Western FC, one of three clubs to open new stadiums this season.

According to Sothea, bringing in good quality foreigners promises improvement among Cambodian footballers, as well as the potential to profit when they are sold on.

“It’s not only for the money, but the performance. Different [footballing] cultures between countries allow us to gain many benefits,” he said.

Another of the clubs to have opened a new stadium is Cambodia’s most widely supported team, Phnom Penh Crown.

With a pristine training pitch beside its 6,000-capacity ground in northern Phnom Penh and a live-in academy for youth players, the club’s set-up stands out among its competitors.

Phnom Penh Crown FC players at training on Tuesday. Victoria Mørck Madsen

Even the academy is buoyed by foreign talent, with two young players from Sierra Leone and another from the pacific island of Vanuatu currently among the under-18 squad, which is competing in this year’s Asia Champions Trophy, an international tournament.

Yet despite the facilities it can offer and its ability to pay some of the highest wages in the country, Phnom Penh Crown’s foreigners also have their eyes on the horizon.

“My goal is not to stay in Cambodia, it’s to go forward,” said 26-year-old South African winger Shane Booysen.

Arriving in Cambodia from Thailand seven months ago, Booysen was originally lured to Southeast Asia by the region’s less aggressive football culture as he continued to recover from knee surgery.

But when a personnel change at his club in Thailand left him surplus to requirements, he found himself in need of a new club.

“When they changed their coach, the transfer window was closed, and the only place that it was still open was Cambodia,” he said.

A collection of Western FC players relax in the stands. Victoria Mørck Madsen

But according to Booysen, despite arriving in Cambodia out of necessity, the standard he has encountered is higher than he expected, as is the level of support from fans.

“It’s nice to see, as a foreigner, the passion for football in Cambodia, because I never knew about Cambodia,” he said.

A risky game

Yet beyond the gradual advances being made in Cambodian football, as well as a spike in the sport’s popularity after the national team this year reached the second round of Asia’s World Cup qualifying for the first time, some deep flaws in the system remain.

Chief among them is medical coverage, with a number of players saying their team did not provide full medical insurance, while some said they were provided none at all.

“The club helps, but there is a limitation to the budget,” said one player, who preferred not to be identified when speaking about the subject.

“Medical care is a very, very big problem,” said another player. “Good care is very expensive and the clubs only pay if it’s cheap and easy. It’s not reimbursed.”

According to Football Federation of Cambodia (FFC) deputy secretary general May Tola, while clubs must present medical certificates proving the fitness of any players they sign, financial constraints prevent the FFC demanding full coverage from all clubs.

Billy Baarnart - Victoria Mørck Madsen

“Our football is still semi-professional,” he said. “So we cannot impose that the club must provide insurance for all of the players.”

Nevertheless, Tola said medical insurance remained an area where the FFC wished to push for improvements, with guaranteed coverage for national team players a possible first step.

“When you are talking about insurance in Cambodia, not just for footballers, but for the whole country, it’s something that is still new,” he said.

But the lack of insurance does not seem to deter foreigners from entering the pitch.

“I want to play for another 10 years,” said Fukasawa, the 38-year old midfielder, who missed an entire year earlier in his career with a serious knee injury.

“In Japan, there is a 48-year-old striker, and he is still scoring goals,” he said, referring to 1990s superstar Kazuyoshi Miura, who still turns out for second-tier Japanese side Yokohama FC.

“I am still among the best runners on the team.”

Contact PhnomPenh Post for full article

SR Digital Media Co., Ltd.'#41, Street 228, Sangkat Boeung Raing, Khan Daun Penh, Phnom Penh, Cambodia

Tel: +855 92 555 741

Email: webmasterpppost@gmail.com

Copyright © All rights reserved, The Phnom Penh Post