Brick by brick, a construction worker cements together a wall of a building in Tonle Bassac commune in Daun Penh district. Heng Chivoan

The capital city is facing a surge in vacant retail space, a figure that has been expanding over time but with the onslaught of food delivery apps and e-commerce, and the ongoing risk of Covid-19, how will it all pan out?

A while ago, businesses started to disappear from WB Arena, a sprawling $10 million riverside development in the capital’s Chak Angre dust swirling commune as the effects of the Covid-19 pandemic dug into people’s pockets.

Built by logistics tycoon Sear Rithy’s development arm Worldbridge Group (hence the WB acronym), the project had Singapore’s famous Clarke Quay in mind when draft plans were drawn up, with the hope of evoking that quayside feel.

The commune, although 3km away from the commercial business district linked by Norodom Boulevard, a thoroughfare flanked by Phnom Penh’s classy old real estate, is an antonym to that upmarket ambience.

Travelling on that road, the 6,000 square metre-leasable space hub including a 400-seat theatre, fronting the scenic Tonle Bassac, breaks the monotony of National Road 2’s ubiquitous mish-mash of a shophouse landscape. The arena was built to provide an all-inclusive entertainment and shopping experience for people in the area without having to go into the city centre.

However, a few short months of its launch in late 2019, businesses came under pressure as footfall waned on the back of an intermittent spike in coronavirus cases.

These days, it languishes with several units, once tenanted by foreign retail chains such as Japanese-owned convenient shop Aeon MaxValu Express and Thai-bred Inthanin restaurant, emptied out while other businesses get by with fewer customers.

Managing director Simon Griffiths of The Mall Company, which oversees a $20 million retail asset portfolio in Cambodia, including WB Arena said occupancy used to be 68 per cent prior to Covid-19.

New tenants were ready to set up shop and a list of marketing activities and events was planned when the pandemic forced a pause on it, dragging occupancy down to 50 per cent.

He said Aeon MaxValu Express’ departure was possibly linked to downsizing efforts. “Their sales target was high even with rental discounts [however] I understand it is not the only store they closed, moved or downsized,” Griffiths told The Post via email.

As for Inthanin, an eatery wholly-owned by Bangchak Retail Co Ltd, he believed that the chain’s popularity was low in Cambodia, seeing that only few stores remained after its initial large expansion plan.

Recently though, its Thai-listed parent Bangchak Corp Plc, with 39.04 per cent equity owned by Thailand’s Finance Ministry and two sovereign bodies, noted that 100 additional stores would be established in Cambodia and Laos, a plan that was delayed due to the pandemic.

But the slowdown has been palpable despite discounts. On the whole food and beverage retail front, Griffiths said discounts of 20 to 70 per cent had been continuously offered depending on the situation and the retailer’s finances as well as the location of the store.

He said given that each store is different, a “blanket” discount policy was not implemented, citing that Starbucks on the street front at Noro Mall would require less discount than a store inside the building, say one located on the second floor.

As the effects of the pandemic eased up in the first two months of this year, discounts were reduced “step-by-step” but things changed again when the third community transmission broke out in the capital.

“For example, Aeon [Mall] is virtually empty at present and [it] is in the central city,” said Griffiths, whose firm also provides retail design consultancy on approximately $40 million worth of retail-focussed developments in the pipeline.

In fact, the firm was ready to sign on Acleda Bank Plc and Volcano Hot, a local soup and barbecue restaurant, at WB Arena, which would have pushed up occupancy to 58 per cent but the tenants decided to hold off until the situation improved.

Dark kitchens and digital apps

The slowing consumption at physical shops is largely a phenomenon of Covid-19 and perhaps to a small extent, a consequence of rising e-commerce and food delivery apps.

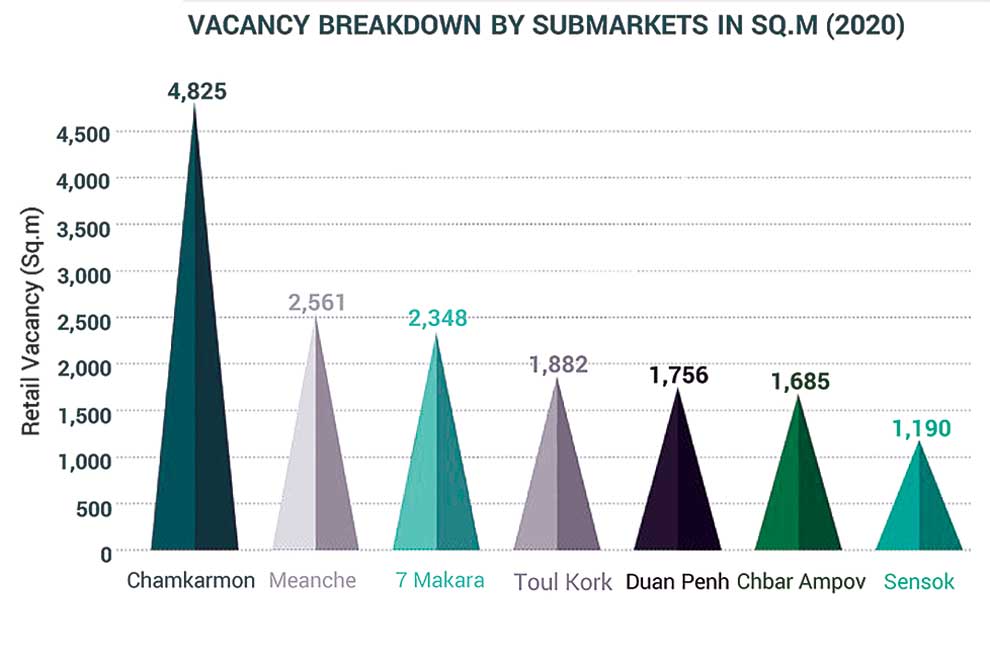

Source: Retail insights, fourth quarter of 2020, The Mall Company

Despite the comparatively small population, these foreign and homegrown apps have flooded the market, and even more so during the pandemic.

It is generally symptomatic of high liquidity in the market and healthy disposable income on the back of an expanding middle-income segment.

This is evidenced by a burgeoning broad money, which was about $29.2 billion in 2019, representing 108 per cent of gross domestic product (GDP) that year.

In the meantime, GDP per capita has risen to $1,643 in 2019 from $738 in 2009, according to the World Bank.

For some businesses, particularly food and beverage operators, serving customers via digital platforms helped them sustain in the downturn, as in the case of Park Café Food and Beverage Co Ltd, a locally-bred food chain.

General manager Heng Sengly said sales had dropped about 60 per cent since the latest wave of community transmission but online orders only dipped marginally.

“If things get severe as they did in Italy or China, we would have to close the shops as a last resort and accept orders for delivery and takeout,” he was quoted as saying in The Post last week.

From the outset of the pandemic, dark kitchens have mushroomed in some of the quieter neighbourhoods in the city to cater to late night food orders.

These kitchens with no signboards or exterior lighting are commonly present in converted porches with food delivery riders camped outside awaiting made-to-order meals as the aroma permeates the streets.

Perhaps, a shifting trend to safer dining for the consumer and lower operating costs for the seller, Griffiths, who agreed that it is an interesting concept, was steadfast in his belief that it would not dent the F&B retail sector.

“… with no store, how does one establish a brand, customer loyalty and following?” he asked.

There are “hundreds and hundreds” of stores now on delivery food apps such as Nham 24, Food Panda and Muuve, and it is difficult to be noticed, and to gain credibility and reputation, he said, adding that stores are valuable brand advertisements.

“... opening a dark kitchen without a store, brand or [physical] customers, [still meant that] marketing costs could easily reach the costs of a physical store if you are going to become well-known and generate a sizeable customer base,” he said.

Griffiths acknowledged that times are difficult and people are driven to online food orders but that would not always be the case.

The apps should be used to supplement store sales with stores turning into distribution points.

“It would be more sensible to look at reducing store size with less seating and focussing on a strong digital presence and strategy rather than going dark.

“I would not recommend setting up a dark kitchen as a way to reduce costs as I don’t believe long-term brand loyalty will be achieved or [that] enough awareness is generated to justify even the cheaper costs of a dark kitchen versus a store,” he said.

It is a notion shared by CBM Corp Co Ltd co-founder Kouch Sokly, whose firm has brought in several international F&B chains including Korean bakery brand Tous les Jours.

Recently, the company has been pushing for more onsite delivery services as customer numbers dwindled, weighing upon its revenue.

However, getting on digital food apps, while it helped to keep the brand and business alive, proved to be a costly affair because of steep commissions.

“It can be as low as 10 per cent and as high as 25 per cent. We only [see] a small [profit] margin because of the high commission fees,” he told The Post via a social messaging app.

Nevertheless, the company continues to invest into the business to sustain an income “from any corner”. “Most importantly, we need to survive this period,” he said.

Tapas Kuila, a former general partner of venture capital firm Ooctanewhich invested in food delivery star-up Muuve, concurred that online food orders have swelled as “more and more people tend to do so instead of dining out”.

In Phnom Penh alone, the gross merchandise value for the food delivery market stands around $16 million to $18 million annually.

But, a majority of the growth has been thanks to Covid-19, which makes it unsustainable, he said, noting that this could be further validated by observing the trends.

“If you look at the volumes in deliveries – food, groceries and couriers – they spiked really high in the initial coronavirus scare back in March and April but it went down to previous levels soon after,” he explained.

What about e-commerce? Does it pose a challenge to the retail market? Griffiths again dismissed the idea that it would threaten physical stores as the entrepreneurial spirit and people’s desire to enjoy retail shopping would see retailers rebound quickly.

He said well-operated e-commerce platforms supplement physical store sales and are valuable assets in the present time to maintain store cashflow.

Asked if the current online shopping trend would persist as things got better, Tapas opined that when it comes to e-commerce, there is a different angle of logistics in the picture, and today, customer experience is “broken and bad” when it comes to that.

“So I think if a company is able to provide that kind of end-to-end good customer service and stickiness from a supply chain perspective, e-commerce volumes could stay the same or subside by a lesser proportion than food deliveries when the economy opens up and hopefully continue on its growth trajectory,” he said.

However, as more retail space, categorised as shopping mall, community mall, retail podium and retail arcade, comes into the market, the pressure of filling them will likely intensify.

Source: Retail Insights, 4th quarter of 2020, The Mall Company

No further rental compression

Figures shared by The Mall’s retail insight showed that Phnom Penh’s vacant retail space rose 85 per cent year-on-year to 16,247 square metres (sqm) as at end-December, 2020, whereas total retail space supply stood at 370,781 sqm last year.

Out of the vacant space, F&B accounted for 58 per cent, followed by fashion (21 per cent) and health and beauty (nine per cent).

In addition, community malls saw the highest unoccupied retail space at 9,565 sqm, ahead of shopping malls (3,091 sqm) and retail podiums (2,351 sqm).

The periodical total net lettable area (NLA) figures often vary a little among real estate service providers, ranging between 50,000 sqm and 100,000 sqm, when compared.

But the anxiety of oversupply in a soft market is staple, judging from the approximate total value of vacant retail space which comes in at $85 million to $105 million as of December 31, 2020.

Headline rental estimate for vacant retail space, a rent that is paid following a rent-free or reduced rent period, stands at $780,000 per month, notwithstanding the impact of additional incentives offered by landlords.

Industry players contend that the figure has improved a little compared to 2015 to 2017 but lament that it is still marginally higher than 2018 and 2019.

“There has not been a significant amount of variance over that period,” one source said.

What this shows is that rental rates on average across Phnom Penh has suppressed 20 to 30 per cent from pre-Covid-19 levels.

At some retail properties, rents have remained stable with zero to 10 per cent drop while at others, as much as 50 per cent lower rates were experienced, Griffiths shared.

That said, he does not foresee rental rates coming down further, anticipating it to stay subdued for most parts of 2021 with some potential gains similar to 2019 in the final quarter of this year.

Overall, some 500,000 sqm NLA of retail supply will stream into the market between now and 2023, UK-headquartered real estate consultant and agent Knight Frank’s statistics showed. By then, total NLA would have ballooned to 909,008 sqm.

Similarly, CBRE Cambodia, an affiliate of US-based commercial real estate services and investment firm CBRE Group Inc, which recorded just over 400,000 sqm of retail supply in Phnom Penh last year, sees a strong uptick in vacant spaces, particularly in retail podium and shopping malls in 2021.

Pre-pandemic development plans

While the numbers are heady in the present economic landscape, it should be noted that these developments were planned at a time when GDP growth averaged seven per cent year-on-year.

Following a record contraction of 3.1 per cent in 2020, the government projects growth to be around 3.5 per cent, slightly modest from National Bank of Cambodia (NBC)’s four per cent forecast this year.

Source: Fearless Forecast 2021, CBRE Cambodia

The pandemic aside, the rise in retail space would be seen as a sign of economic growth, especially where real estate and construction largely underpinned Cambodia’s gross domestic product in recent years.

Foreign direct investment in this sector in 2019 represented 18.6 per cent of the total $3.7 billion, up 13.7 per cent from 2018, with a majority of that from mainland China and greater China including Taiwan and Hong Kong.

In the meantime, local developers stepped up to be on par with foreign players to meet a robust housing, retail and office demand, signalling Cambodia’s position at the cusp of a massive economic growth.

Having said that, it also raised NBC’s anxiety of a property bubble due to the rapid and staggering expansion of the sector as real estate financing and mortgages, offered by developers, grew unchecked.

In the midst, incessant constructions retail arcades in the last five to six years continued with some running into financial trouble even before the pandemic.

They include the market redevelopment of Century Plaza by Chinese investors on Russian Federation Boulevard and the long-overdue Phnom Penh Mega Mall on Street 271, which has allegedly restructured its loan. Together, these projects command a gross development value of $120 million.

A weary outlook

This circles back to the challenge that has commonly plagued the sector over the past years, which as Ross Wheble, country head for Knight Frank (Cambodia) Pte Ltd, said is the disequilibrium between supply and demand.

Drawing a parallel, he said due to the surge of incoming mall completions during the second half of 2020, average occupancy rate had compressed further to 79 per cent, a six percentage point year-on-year drop since 2019.

Contending that footfall traffic has fallen intermittently due to viral outbreaks over the past year, Wheble noted that there were no mass foreclosures of major retailers evident in the second half of 2020.

However, foreclosures among stand-alone traditional shophouses converted for use as retail started to rise, owing to a drop in incoming tourists which formed the bulk of their clientele.

Still, overall consumer appetite would undoubtedly keep the retail real estate sector buoyed, because of increasing disposable income, said James Hodge, managing director of CBRE Cambodia.

He also reminded that retail space per capita in Phnom Penh was among the lowest among major cities, if not the lowest, in Southeast Asia at less than 0.2 sqm.

In comparison, Yangon in Myanmar recorded nearly 0.7 sqm of completed retail space per capita whereas Vientienne in Laos pushed slightly above 0.3 sqm.

Coupled with its young population and growing spending money, strong interest has piqued among popular brands, with Asia Pacific labels leading the way.

It represented new entrants at 61.3 per cent in the fourth quarter of 2020, towering over those from Europe, the Middle East and Africa (25.8 per cent) and the Americas (12.9 per cent), Hodge said.

Nearly two-thirds of that figure constituted F&B businesses, such as milk tea, Korean and Japanese restaurants, fast food and dessert shops, while the rest were fashion and accessory outlets - which grew 100 per cent from 2019.

“As such, we expect that the sector would continue to diversify its offerings in order to widen the pool of potential customers, and drive footfall and retail spending,” he added.

At the same time, a fraction of developers have started to resolve the problem of vacant units themselves either by repurposing them or in the case of well-capitalised owners – bringing in and operating brands themselves.

“[It] ensures good occupancy rates in the malls. As more malls are established across the capital, the market becomes attractive to major retail powerhouses such as Uniqlo and H&M. We should see new entrants into the market,” said Wheble of Knight Frank.

As for older properties such as the Bayon Market building near Russian Federation Boulevard and Pencil Mart on Samdech Pan Street, which is one of the oldest malls in the city, they have been repurposed as low-rent office buildings.

Similarly, $15 million Young’s Commercial Centre and Resort Co Ltd in Chroy Changvar is now New City Walk after it was sold, having not achieved its original vision as a one-stop mall within the Happiness City mixed-development project. It was redesigned into retail and office units, and relaunched.

Meanwhile, some projects are progressing slowly or are delayed, though it is “hard to tell”, The Mall’s Griffiths confessed.

“We know of six small to medium-size retail projects, each with less than $8 million GDV that have been put on hold. However, they are at the early design and development stage, so it is easy to hold at that stage,” he said.

But what is to come of all this, is unclear. Real estate agents show relative optimism, acknowledging that “everyone is struggling” but at the core of it, the amount of vacancy remains a huge reckoning for the real estate sector.

The short-term outlook is likely to be weary as supply piles on, doubling present figures, assuming all projects complete as scheduled, Knight Frank wrote, but could it last longer? Only time will tell.