Most of Cambodia’s FDIs in recent years has been the area of construction and real estate. Heng Chivoan

As the sector expands, allegations of financial institutions engaged in unconventional activities continue to show up like a bad debt

‘A lot of it involves their own project financing,” an industry player spoke in hushed tones over how the burgeoning banking sector sustains itself.

“Some banks are set up by large-scale foreign investors with billion dollar projects in Cambodia to channel their funds,” he said. “The banks also own equity in the projects, at times.”

One of the ways is to provide collateralised overdraft facilities that run into millions to investors.

“That way, the investor need not drawdown its capital investment, allowing it to instead earn interest from fixed deposits,” he said.

The growth of banks in Cambodia has been brow-raising if not ironical, seeing that some 70 per cent of the population is unbanked.

There are 52 commercial banks and counting, 81 microfinance institutions including microfinance deposit-taking institutions (MDIs) while specialised banks make up 14, as of August 31, 2020.

Separately, there are scores of pawn shops and unlicensed money lenders dotted around the countryside offering small but instant microfinance credit.

Out of the 52 commercial banks, only 22 are locally-incorporated and of that just a handful are established by Cambodians as the others are foreign-owned.

Difficult to say how banks make their money when the market is small, In Channy said. Hean Rangsey

Cambodia’s economic boom in the last 10 years and favourable business conditions where foreign parties are permitted to wholly own companies and remit their profit home, makes it a magnet for investors.

In the past, massive investments went to garment, footwear and travel goods manufacturing as the US and EU granted preferential tariff schemes in 1997 and 2001, respectively.

Later on, real estate, construction and public infrastructure investments rolled in on the heels of China’s Belt and Road Initiative.

These investments, approximately $85.9 billion between 1995 and 2019, also heralded the entry of financial institutions.

“The fact that it is a highly dollarised open economy also attracts foreign direct investment (FDI) in the billions compared to regional peers,” said the banker, who requested anonymity due to the sensitivity of the subject. “The market is flush with cash, hence the rise in banks.”

Essentially, a number of the banks were set up solely to serve their own self interest, either to finance their projects and group operations, and as a conduit for financial transactions.

Some foreign-owned banks also cater to investors from base countries.

To give an idea, real estate and construction FDIs were among the largest in the recent years, as the country dug into development as a means to build the nation.

Some 50 per cent of the total FDI originated from China and its greater region, with half of that invested in those two sectors, the World Bank said in May.

For instance, Chinese property developer Prince Group, one of the major players in the real estate industry, has poured in $2 billion since its debut in Cambodia in 2015.

Over time, the conglomerate expanded to include aviation - where it owns an airline - hospitality and banking.

“For Prince, their own projects can sustain their banking business,” the banker said.

Questions to Prince did not elicit a reply.

The banker claimed that homegrown banks such as Canadia Bank Plc, Chip Mong Commercial Bank Plc and Vattanac Bank Plc, with roots in real estate and construction, most likely enjoyed a significant revenue stream from this business segment although their core business remains in consumer banking facilities.

But this here brings to question the issue of profitability and solvency for the entire sector as the growth of banks starts to crowd the market.

It also questions the type of business the banks conduct to survive, especially if they all claim to do the same business.

On average, the National Bank of Cambodia (NBC) noted that profitability, represented by a return on asset and return on equity, improved by 1.9 per cent and 9.8 per cent year-on-year, respectively, in 2019.

The central bank’s Annual Supervision Report last year also showed that solvency ratio stood at 24 per cent while liquidity coverage ratio was 155.7 per cent, reflecting overall stability.

Having said that, Stephen Higgins, co-partner of Mekong Strategic Partners Co Ltd who authored a review on the sector titled Time for Consolidation, said around 20 per cent of banks reported losses in 2019.

“But [some] 80 per cent earned a return on capital that is subeconomic,” he told The Post.

Commercial bank operating licence granted by the NBC enables banks to give out loans and earn interest to raise revenue, mobilise savings and use it to fund projects, and provide fund transfer service.

“But how do they make money? It is difficult to say because there are too many banks [fighting] for market share,” said In Channy, chairman of the Association of Banks in Cambodia.

Citing the example of his bank, Acleda Bank Plc, where he is the president and CEO, Channy said its customer loans and deposits make up about half its bank portfolio.

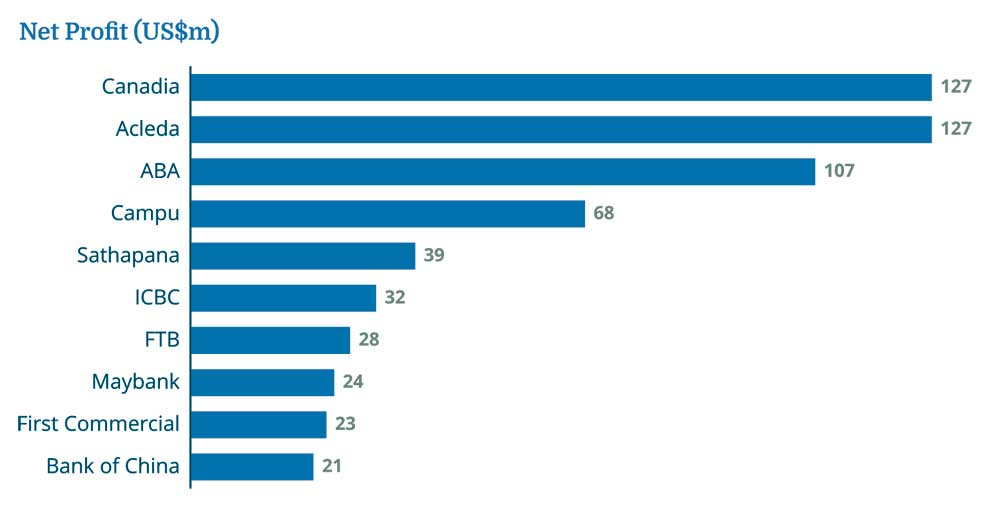

Source: NBC 2019 Supervision Report and MSP analysis (2019)

“Our loan volume in terms of dollars is 16 per cent of the overall market share while savings represented 17 per cent. This is the major business of our bank,” he added. “Cambodia is a small country [where] five to six banks are okay but now we have 10 times more.”

As it stands, Cambodia’s population is about 16 million with an adult population of around 10 million.

In 2017, the World Bank said only 22 per cent of those aged 15 and above had a bank account which leaves the rest of country unbanked.

However, they are highly leveraged, owing to staggering loans from microfinance institutions, which have resulted in an outstanding debt of $10 billion.

Echoing Channy, David Van said despite being a “such a tiny market”, Cambodia constantly saw new commercial banks.

“[It] is a real mind boggling fact unless these many banks have a magic formula for their intended clientele,” said the senior associate (private public partnership) of Platform Impact, an investment platform which owns seven portfolios valued at $200 million.

However, he felt that local commercial banks are conservative and lack in-house expertise to handle risk management for trade financing of commodities trading for exporters.

“In addition, major loans still remain dispensed against traditional collateral. They do not possess the same modus operandi and mentality of investment banks which have yet to operate in Cambodia,” Van added.

Some weeks ago, the NBC granted an approval-in-principal for a new commercial bank, Oriental Bank Plc, which has links with Kuala Lumpur-listed renewable energy developer G Capital Berhad.

According to majority stakeholder Phan Ying Tong, who was quoted by The Star publication in Malaysia, Oriental Bank would engage in digital and conventional banking.

Phan, a banker with over 40 years experience, said the strategy was to capture the market share of the tech savvy consumers as well as those who preferred brick-and-mortar banking.

He pointed out that studies found that a stronger focus into digital solutions would enhance a bank’s profitability, perceived value, convenience, functional quality and service quality.

But surely all this comes at a price, and one that presses on the bottomline, seeing that digital transformation is the direction most banks are adopting for long-term survival.

And often, the larger banks tend to scoop up the bigger share due to their existing prominence in the field and spending capacity.

In his review, Higgins wrote that out of the total commercial banks, the `big five’ accounted for 57 per cent of market revenue last year, which has been stable over the past five years.

Source: NBC 2019 Supervision Report and MSP analysis (2019)

He said Acleda Bank stayed on as market leader with 19 per cent revenue share, although it was a decline from 28 per cent in 2015.

In that same period, Canadian-owned Advanced Bank of Asia Ltd (ABA Bank)’s revenue share climbed to nearly 14 per cent from four per cent.

“Below the big five banks, the next 20 account for 35 per cent share of revenue [and] below that, the bottom 35 banks account for just eight per cent,” he said.

This disposition has always been riddling as it blows open the predicament of how the other banks are sustaining. It is also here where speculations of money laundering mire the industry’s image.

According to the anonymous banker, much of the money allegedly flows through various channels including shell companies before settling in banking accounts in the Kingdom where they are used to fund projects, among other things.

“On paper these transactions are above board while being closely monitored by the NBC but you know there are ways to do things,” he trailed off.

He cited the 1Malaysia Development Berhad financial scandal, which spanned the globe, as an example of how despite ample checks and balance in the financial sector, illicit transfers from offshore accounts still managed to hoodwink strict banking rules.

“It is all down to a sleight of hand in accounting,” the banker alleged.

It does not help that Cambodia remains grey listed by the Financial Action Task Force for lacking legal frameworks to tackle money laundering.

This is compounded by the rise in casinos, up to 150, which the UN Office on Drugs and Crime alleged in 2019 that it was linked to locations, such as those in Phnom Penh and Cambodia’s borders, for “bulk cash smuggling and the laundering of organised crime revenues”.

Swiss-based independent Basel AML Index also revised Cambodia’s ranking upwards to 11 out of 141 countries on August 7, 2020 from 16 in 2019, with a 7.1 risk score out of 10.

Source: NBC 2019 Supervision Report and MSP analysis (2019)

However, the NBC has instituted safeguards including the creation of the Cambodia Financial Intelligence Unit while the government recently strengthened the 2007 Law on Anti-Money Laundering and Combatting the Financing of Terrorism.

It also launched a five-year national strategy to combat the scourge.

Additionally, by the first half of this year, some 140 money laundering cases were probed and 22 were sent to court while the assets of the individuals were frozen. Five cases have gone on to trial, the Ministry of Information said in October.

These improvements have been reviewed by the FATF in June and Asia Pacific Group on Money Laundering in October, which authorities hope would put a positive spin on Cambodia’s grey listing status.

But in the midst, the banking sector continues to expand, kicking up speculations of these alleged links to the underground world.

For Higgins, the growth draws a blank, saying that there are too many small banks that do not have scale to properly compete. “I don’t understand why anyone would start a new bank here. Buying one of the larger, higher quality operations would make a lot more sense.”

How about the existing ones, some which remain in the shadows, almost unheard of?

“Most of the small banks would be better off taking their shareholders’ funds and putting it on deposit at one of the bigger banks or MDIs. They would get a much better return,” Higgins opined.

Although, what is clear is the call for consolidation which can inadvertently strengthen the sector, weed out illicit activities and enable stringent monitoring.

Even the NBC made implicit moves to integrate the sector when it doubled the paid-up capital requirement for commercial banks to $75 million and specialised banks to $15 million in 2016.

Source: NBC 2019 Supervision Report and MSP analysis (2019)

The increase for MDIs was most glaring at $30 million versus $2.5 million previously.

Interestingly, most of the banks complied with the order while some even surpassed the requirement, backed by their foreign parents. No merger has happened, unfortunately.

Higgins said NBC should consider raising the minimum capital requirement to $150 million by 2025.

A typical bank with $75 million capital could only build a maximum loan book size of about $400 million or below 1.5 per cent market share of the overall financial sector loans in 2019.

Source: NBC Annual Supervision Report 2019

It could fall to less than one per cent share by 2023, which would call into question the viability and relevance of banks of this size.

“The higher capital would strengthen the overall health of the banking sector, and encourage much needed consolidation to reduce the number of banks under 60,” he said.

But consolidation, dictated by the market, will definitely happen, the banker prophesised.

“It is in the natural course of things. The simulation here was present in other countries in the region, such as Singapore and Malaysia which had tens of banks in the 1990s but they eventually consolidated.

“It won’t always be like this,” said the banker.